The complete aromatic perception of a chocolate hinges not on taste, but on mastering the release and capture of its volatile compounds through controlled temperature and breathing techniques.

- Slightly warming chocolate brings it closer to its melting point, increasing the kinetic energy of aroma molecules and allowing them to become airborne.

- The technique of retronasal olfaction—exhaling through the nose while the chocolate is in your mouth—is essential for transmitting these aromas to your olfactory receptors.

Recommendation: To fully map a chocolate’s profile, consciously manage its temperature, use a tulip-shaped glass for hot preparations, and practice active retronasal breathing to experience the full aromatic journey from attack to finish.

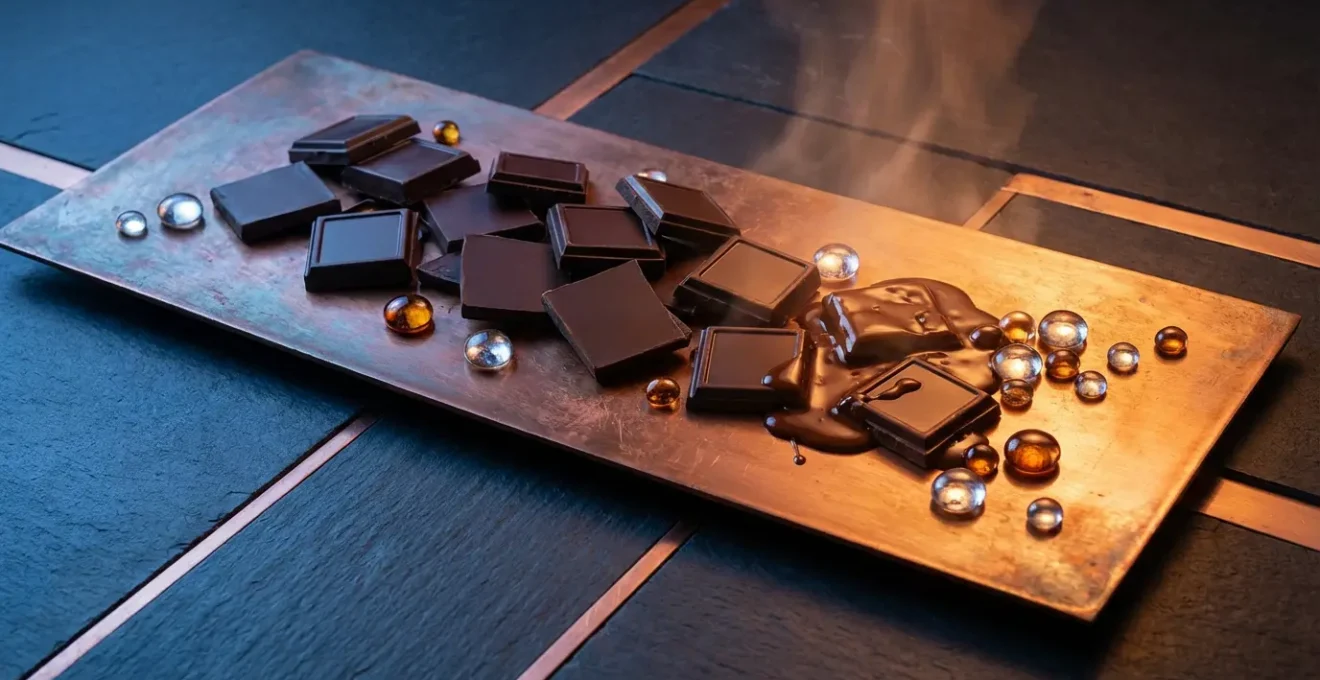

The experience of fine chocolate is an ethereal dance, a fleeting performance of aromatic notes that many of us only partially perceive. We are often told to simply let it melt on the tongue, assuming that taste is the primary vector of pleasure. This common approach, however, overlooks the most critical instrument in a taster’s sensory orchestra: the nose. The perception of flavor is predominantly an olfactory event, a subtle interplay between temperature, air, and the complex chemistry locked within the cocoa bean. True appreciation goes far beyond the simple sensations of sweet or bitter detected by the tongue.

Most guides focus on pairing or percentage, but they rarely delve into the physics of aroma release. They fail to explain why the same piece of chocolate can reveal a shy floral note one moment and a bold roasted profile the next. The secret lies not just in the chocolate itself, but in how we prepare ourselves and our environment to capture its most ephemeral messages. The difference between a pleasant snack and a profound tasting experience is the conscious orchestration of this aromatic choreography.

But what if the key was not merely to warm the chocolate, but to actively manage the journey of its volatile molecules from the solid state to your olfactory bulb? This guide moves beyond the platitudes to explore the science of aroma perception. We will uncover how to transform a simple act of eating into a deliberate technique for unlocking the full, hidden bouquet of any chocolate. By understanding the roles of respiration, containment, and molecular volatility, you will learn to hear every note in the chocolate’s aromatic symphony.

This article will guide you through the essential techniques and scientific principles that allow an expert taster to perceive the entirety of a chocolate’s aromatic profile. We will explore how to use your breath as a tool, select the right vessel to concentrate scents, and identify flaws before they even reach your palate, mapping the flavor journey from its initial attack to its lingering finish.

Summary: Unlocking the Full Aromatic Potential of Chocolate

- How to Exhale Through Your Nose While Eating to Unlock Hidden Aromas

- Wine Glass or Wide Cup: Which Container Concentrates the Scents of a Hot Chocolate?

- Smoky or Musty: How to Spot a Drying Defect Before Even Tasting?

- The Mistake of Wearing Strong Perfume That Cancels Out Your Tasting Ability

- Floral vs. Earthy: Why Do Some Aromas Evaporate Faster Than Others?

- Why Does a Too-Fast Roast Destroy Floral Aroma Precursors?

- The Aeration Error That Kills Subtle Notes of Yellow Fruits

- How to Map the Flavor Journey from Attack to Finish?

How to Exhale Through Your Nose While Eating to Unlock Hidden Aromas

The vast majority of what we call “flavor” is, in fact, aroma. While our tongues are limited to five basic tastes (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami), our noses are capable of discerning a staggering array of scents. Chocolate is a universe of aromatic complexity; indeed, research from Munich Technical University reveals that over 600 volatile compounds contribute to its signature smell. The key to accessing this library of scents is not through sniffing the bar directly (orthonasal olfaction) but through a more intimate pathway: retronasal olfaction. This is the act of perceiving aromas that travel from the back of your mouth up into your nasal cavity as you eat and exhale.

The technique is simple in theory but requires conscious practice. As a piece of chocolate melts in your mouth, its warming cocoa butter releases trapped volatile molecules. By gently and slowly exhaling through your nose with your mouth closed, you create an air current that carries these fragrant molecules directly to your olfactory epithelium. This is where the magic happens. The brain combines the signals from your taste buds with this rich aromatic data, constructing the complex and nuanced perception we call flavor. Without this step, you are only experiencing a fraction of the chocolate’s potential.

This mechanism is so fundamental that it often creates a sensory illusion. As neuroscientist Dana M. Small of Yale University explains, this process is profoundly deceptive in its elegance. It convinces us that the entire experience is happening on our tongue.

The illusion that retronasally perceived odours are localised to the mouth is so powerful that people routinely mistake retronasal olfaction for taste.

– Dana M Small, Yale University neuroscience research

Mastering this active breathing technique transforms you from a passive consumer into an active participant in the aromatic choreography. You are no longer just tasting; you are directing the flow of information, ensuring that every subtle hint of fruit, flower, or spice is given a chance to perform on your sensory stage.

Wine Glass or Wide Cup: Which Container Concentrates the Scents of a Hot Chocolate?

When tasting liquid chocolate, the vessel is not a mere container; it is an instrument for shaping the aromatic experience. Just as a wine connoisseur selects a specific glass to enhance a vintage’s bouquet, a chocolate expert must consider how the shape of a cup influences the concentration and delivery of volatile aromas. The critical factor is the relationship between the surface area of the liquid and the volume of the space above it, known as the headspace. A wider surface allows for more aromas to be released, while a narrower opening concentrates them, directing them towards the nose.

This concept is best visualized by comparing three common shapes: a standard wide cappuccino cup, a tulip-shaped glass (like a small snifter), and a wine glass. The illustration below demonstrates how steam, carrying the volatile aromas, behaves differently in each.

As you can see, the wide, open cup allows aromas to dissipate quickly into the surrounding air. While pleasant, it provides a less focused olfactory experience. In contrast, the tulip-shaped glass or a wine glass is far superior for analytical tasting. The wider bowl allows the hot chocolate to breathe and release its full spectrum of scents, while the inwardly curved rim narrows the opening, capturing and concentrating these delicate effluves. As you bring the glass to your lips, this concentrated cloud of aroma is delivered directly to your nose, providing a powerful and detailed preview of the flavor profile before the liquid even touches your tongue.

The choice of vessel becomes an active part of your tasting ritual. For a casual, comforting experience, a wide mug is perfectly fine. But for the expert seeking to dissect and understand the full aromatic architecture of a fine hot chocolate, a vessel with a wide bowl and a tapered opening is an essential tool. It transforms the act of drinking into an immersive olfactory event, ensuring no subtle note is lost.

Smoky or Musty: How to Spot a Drying Defect Before Even Tasting?

Before a chocolate’s desirable aromas can even be appreciated, an expert taster must first learn to detect the undesirable ones. Many of a chocolate’s most significant flaws do not originate in the final stages of production but much earlier, during the critical post-harvest process of drying the cocoa beans. Improper drying can introduce persistent, unpleasant off-notes that no amount of skillful roasting or conching can fully erase. The two most common culprits are smoky flavors from open-wood-fire drying and musty or moldy notes from slow, overly humid drying conditions.

These defects are caused by specific chemical compounds that your nose is remarkably adept at detecting, often at very low concentrations. A smoky taint, for instance, is typically caused by phenols and cresols that are absorbed by the beans when dried over poorly ventilated fires—a common practice in regions where mechanical dryers are not accessible. A musty, earthy, or “dirty” smell is often linked to geosmin, the same compound responsible for the smell of damp soil, which is produced by microbes that thrive in overly moist environments. Your first interaction with a piece of chocolate—the initial snap and sniff—is your first line of defense against these flaws.

The following case study illustrates how scientific analysis confirms what a trained nose can detect.

Case Study: Linking pH to Drying Defects

Research into chocolate quality control has shown a direct link between the acidity of cocoa liquor and the presence of off-flavors. One analysis of volatile compounds in chocolate found that samples with a lower pH (ranging from 4.75 to 5.19) were significantly more likely to contain high levels of phenols and cresols. These compounds are tell-tale signs of improper drying techniques, such as using direct wood fires, which imparts a harsh, smoky character to the final product. A trained taster can often detect this acrid, phenolic note as a primary aroma before even placing the chocolate in their mouth, identifying a fundamental flaw in the bean’s journey.

Developing the ability to spot these defects “at the door” is a crucial skill. It allows you to identify the source of a flaw and to separate imperfections originating from the raw material versus those from the manufacturing process. A smoky or musty note is a clear signal of a problem at the farm level, and no amount of tasting technique can turn a flawed bean into a first-rate chocolate.

Action Plan: Auditing for Drying Defects

- Initial Snap & Sniff: Break the chocolate near your nose. Does it release a clean “cocoa” scent, or do you detect upfront notes of smoke, damp earth, mildew, or anything acrid?

- Isolate the Aroma: Cup your hands over the chocolate and inhale deeply. Focus on separating the primary scents. Is there a “hammy” or “smoky” character that overpowers the others? Is there a background scent reminiscent of a damp basement?

- Warm in Hand: Rub a small piece between your fingers. The gentle warmth will volatilize compounds. Re-evaluate the aroma. Do the off-notes become more pronounced? A smoky flavor, in particular, will often intensify with heat.

- Compare to a Control: If possible, compare the suspicious chocolate with a reference bar you know to be of high quality. The contrast will often make the defect unmistakably clear.

- Log Your Findings: Note the specific character of the off-note (e.g., “phenolic, like a campfire” or “musty, like wet leaves”). This builds your sensory memory for future tastings.

The Mistake of Wearing Strong Perfume That Cancels Out Your Tasting Ability

The nose is the most sensitive and essential instrument for a chocolate taster, yet it is also the most easily overwhelmed. A common and critical error, even among enthusiasts, is to approach a tasting session while wearing perfume, cologne, or even strongly scented lotion. This introduces “olfactory noise” that can completely compromise your ability to perceive the subtle and complex notes of a fine chocolate. Your olfactory system is not designed to process a multitude of strong, competing aromas simultaneously; instead, it tends to blend them into a single, often muddled, perception.

This phenomenon is not just a matter of distraction; it is a neurological limitation. As neuroscience research indicates, humans have about 400 different receptor types for detecting smells. When these receptors are bombarded by the potent and complex molecules of a synthetic fragrance, they become saturated. This state of olfactory adaptation or fatigue dramatically raises your perception threshold, rendering you “blind” to the more delicate and less aggressive volatile compounds in the chocolate. The faint floral aldehydes or fruity esters in a Criollo bean stand no chance against the assertive power of a designer perfume.

Gary Reineccius, a food science expert at the University of Minnesota, highlights how our brains are wired to simplify, not separate, complex aromatic inputs.

By the time you put four chemicals together, your brain can no longer separate them into components. It forms a new, unified perception that you can’t recognize as any of those individual aromas.

– Gary Reineccius, University of Minnesota food science research

To prepare for a serious tasting, creating a neutral sensory environment is paramount. This means not only avoiding personal fragrances but also being mindful of ambient smells like coffee, scented candles, or cleaning products. Your goal is to provide your olfactory system with a clean canvas, allowing the chocolate—and only the chocolate—to be the artist. Treating your nose with the same respect a musician treats their instrument is a prerequisite for achieving a truly expert level of perception.

Floral vs. Earthy: Why Do Some Aromas Evaporate Faster Than Others?

The aromatic journey of a chocolate is not a static event; it’s a timed-release performance, a ballet of molecules where different dancers take the stage at different moments. An expert taster knows that the first notes perceived are not always the ones that linger. This is because the hundreds of volatile compounds in chocolate have different physical properties, primarily their size and weight. This directly influences their volatility—the ease with which they transition from the chocolate into the air to reach your nose.

Generally, lighter, smaller molecules become airborne more easily and at lower temperatures. These are often the bright, ethereal top notes of a chocolate’s profile. Think of delicate floral aromas (like jasmine or orange blossom), fresh citrus, and light fruity esters (like raspberry or pear). They are the first to be released as the chocolate begins to warm, greeting your nose with an initial, often fleeting, burst of fragrance. They are the sopranos of the aromatic choir, hitting the high notes early.

Conversely, heavier, larger molecules require more energy (i.e., more heat and time) to evaporate. These form the base notes of the chocolate’s profile. This category includes earthy, woody, nutty, spicy, and deeply roasted (pyrazinic) aromas. They are less volatile and tend to anchor the flavor experience, revealing themselves later as the chocolate is fully melted in the mouth and their presence lingers long into the finish. They are the baritones and basses, providing depth, structure, and a lasting impression. The visualization below offers a metaphor for this sequential release.

Understanding this “aromatic choreography” is key to mapping a chocolate’s full profile. It explains why a chocolate might smell floral at first sniff but taste predominantly nutty or roasted. The expert taster doesn’t just identify the aromas; they note their sequence, their intensity, and their duration. This awareness of molecular weight and volatility transforms a simple tasting into a dynamic, four-dimensional experience, allowing you to appreciate the full, unfolding story the chocolate has to tell.

Why Does a Too-Fast Roast Destroy Floral Aroma Precursors?

The aromatic potential of a chocolate is not a given; it is forged in fire. The roasting stage is arguably the most transformative step in chocolate making, where hundreds of flavor and aroma compounds are created through a series of complex chemical changes, most notably the Maillard reaction. This is the same reaction that gives bread its crust and steak its savory char. However, in cocoa, this process is a delicate art. A roast that is too hot or too fast can irrevocably destroy the very precursors needed for the most delicate and sought-after aromas.

Floral aromas, in particular, are casualties of an aggressive roast. These scents are primarily derived from compounds called aldehydes, which are either present in the unroasted bean or formed during the early, gentler stages of the Maillard reaction. If the temperature climbs too quickly, these fragile molecules are simply burned off or are never formed at all, as the reaction skips past the necessary intermediate steps. Instead, the roast favors the creation of more robust, dominant pyrazines—the compounds responsible for nutty, roasted, and “chocolatey” notes. While desirable, an overabundance of these can mask or eliminate any subtlety.

The data is clear on this destructive effect. Precise temperature control is not a suggestion; it is a requirement for preserving aromatic complexity. For instance, research on chocolate production chemistry shows that roasting temperatures above 160°C destroy up to 70% of floral aldehydes within just 15 minutes. This is why master roasters often employ carefully profiled, slower roasts, allowing for the full development of a wide spectrum of aromas, from the lightest florals to the deepest roasted notes. As research from Ohio State University confirms, fast roasting bypasses the early reaction stages, preventing the formation of these delicate compounds entirely.

For a taster, this knowledge is crucial. When you encounter a chocolate that is monolithically “roasty” or “chocolatey” with no other discernible top notes, it is often a sign of a generic, high-temperature roast designed for consistency rather than complexity. A truly great chocolate, by contrast, will present a layered aromatic profile, a testament to a roast that was patient enough to cultivate the floral precursors before developing the deeper base notes.

The Aeration Error That Kills Subtle Notes of Yellow Fruits

While aeration can be a tool to open up some flavors, particularly in wine, it is a double-edged sword in the world of fine chocolate. Excessive or prolonged exposure to air can be detrimental, leading to the rapid degradation of some of the most delicate and desirable aromatic compounds. The subtle, sweet notes of yellow fruits—such as apricot, peach, or mirabelle plum—are particularly vulnerable. These aromas are largely created by a class of volatile compounds called esters, which are notoriously susceptible to oxidation.

When you vigorously stir a hot chocolate, or even repeatedly agitate a piece of chocolate in your mouth with too much air, you are accelerating this process of oxidation. Oxygen molecules react with the fragile esters, breaking them down into less aromatic or even unpleasant compounds. This effectively “kills” the bright, fruity top notes, leaving behind a flatter, less complex flavor profile. What might have been a vibrant and multi-faceted chocolate can quickly become muted and one-dimensional.

The impact of over-aeration is not just anecdotal; it is quantifiable. Studies on the chemical composition of chocolate aroma demonstrate a significant loss of these key compounds when exposed to air for too long. For example, volatile compound analysis demonstrates that esters responsible for yellow fruit notes can degrade by 40-60% after just 30 minutes of excessive aeration in a liquid state. This is why a freshly prepared hot chocolate often has a much brighter aromatic profile than one that has been sitting out or has been kept warm on a heating element for an extended period.

The expert taster must therefore approach aeration with intention and restraint. A gentle swirl in the cup to release the initial bouquet is sufficient. When tasting solid chocolate, the focus should be on melting and retronasal breathing, not on creating excessive turbulence in the mouth. The goal is to capture the aromas as they are released, not to subject them to a prolonged and destructive barrage of oxygen. Preserving the delicate notes of yellow fruits requires a gentle hand and an awareness that, sometimes, the best action is to do less.

Key Takeaways

- The majority of “flavor” is perceived via retronasal olfaction, making controlled exhalation through the nose a critical tasting technique.

- A tulip-shaped glass or wine glass is superior for tasting hot chocolate, as it concentrates volatile aromas in the headspace.

- Aromas have different volatilities: light floral and fruity notes appear first, while heavier earthy and roasted notes emerge later and linger longer.

How to Map the Flavor Journey from Attack to Finish

Having understood the mechanics of aroma release and perception, the final skill for an expert taster is to synthesize this knowledge into a coherent methodology: mapping the flavor journey. A chocolate’s profile is not a single, static picture but a dynamic narrative that unfolds over time. This narrative has a distinct structure, typically divided into three acts: the attack (the initial impression), the mid-palate (the core development), and the finish (the lingering aftertaste). Your role is to be an attentive chronicler of this journey.

The journey begins the moment the chocolate enters your mouth. The initial warming from body temperature triggers the release of the most volatile compounds. This is the attack, dominated by the light, fleeting top notes we discussed—the florals, the citrus, the bright fruits. The critical action here is to note these first impressions, as they may not last. The true “engine” of the experience is the melting of the cocoa butter. According to food science research, cocoa butter melts just below body temperature (around 34-38°C), a process that releases the vast majority of trapped aroma compounds in a concentrated burst, typically within 15 to 20 seconds.

This burst initiates the mid-palate, where the core character of the chocolate reveals itself. Here, the heavier, more robust aromas—nutty, spicy, woody, and roasted notes—come to the forefront, supported by the basic tastes detected by your tongue. Throughout this phase, your controlled retronasal breathing is essential to continuously feed your olfactory system with these developing aromas. Food scientists have even developed a methodology called Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) to formally map this evolution. As studies using TDS show, panelists can track which sensation is dominant at any given moment, creating curves that visually represent how the flavor profile shifts from, say, “fruity” to “roasted” and finally to “cocoa” over the course of a minute.

Finally, there is the finish. After you have swallowed the chocolate, what remains? This is the test of a truly great chocolate. The finish should be clean, pleasant, and long. The aromas that linger are typically the heaviest and least volatile. Do you perceive a persistent roasted cocoa note? A hint of spice? Or does an unpleasant bitterness or astringency remain? By consciously paying attention to these three acts, you transform a simple tasting into a structured analysis, creating a complete and detailed map of the chocolate’s unique aromatic story.

By applying these principles of active perception, environmental control, and sequential analysis, you can elevate your tasting ability and unlock the full, breathtaking complexity hidden within every piece of fine chocolate.